|

|

The

VigilanceVoice The

VigilanceVoice

VigilanceVoice.com

v

Monday-- March 4, 2002—Ground

Zero Plus 174

The Sweet Smell of Napalm

by

Cliff McKenzie

Editor, New York City Combat Correspondent News

GROUND ZERO, New York City,

Mar. 4--When the movie screen filled

with roiling balls of orange and black fists of fire and hell, I let

out a gasp, turned to my wife in the darkness of the theater and

reverently said, "God, I loved napalm!"

I was glued to my seat, reliving the past in Randall Wallace's brilliantly

directed We Were Soldiers, a movie from my viewpoint about the

grueling test of men fighting to the death not for God or Country but for

themselves--warriors fighting for the glory of their own survival.

I was glued to my seat, reliving the past in Randall Wallace's brilliantly

directed We Were Soldiers, a movie from my viewpoint about the

grueling test of men fighting to the death not for God or Country but for

themselves--warriors fighting for the glory of their own survival.

"We Were Soldiers," starring Mel Gibson as

Lieutenant Colonel Harold Moore, commander of the 7th Calvary, America's

first airborne attack unit deployed in Vietnam, is void of political

oppression common to most war movies--especially those about Vietnam.

It was not riddled with moral agendas, didn't seek to issue indictments as

to the "good or bad," or the "right or wrong" of war itself--but rather

served as an anatomy of why men fight to the death for their leader, for

their comrades.

I thought it fairly depicted

both sides of the war--the American goal of defending Freedom,

and the North Vietnamese goal of erasing foreign invaders from

their troubled country.

As one of the first U.S. Marine Corps Combat

Correspondent to land in Vietnam in 1965, I was trained to fight and kill

first, and secondly, to write and praise. My mission was to

report the individual heroism of the warrior, to extol the courage,

conviction and action that override a man's fear, intimidation and

complacency when he looks into the face of death.

Some may call me a propagandist, a hack who was

paid to glorify war, to promote the ugliness of destroying others, to

shade the horror of young men dying for some futile political cause.

Those who say those things, or think those thoughts, have never been in

battle, never committed themselves to the protection of their buddies,

never been trained to crawl out in a hail of bullets to drag a wounded

comrade to safety even if such an act meant one's own sure and sudden

death--or at least the highest risk of its occurrence.

"We Were Soldiers" was a well-stated story

of men dying for other men, risking their lives for others on their

team--regardless of their race, color, creed, sexual preference, politics.

It was the purity of brotherhood, the ultimate in the courage of warriors

fighting to achieve victory over fear of death.

September 11th was like that.

Men and women dropped their individual prejudices, bigotries, wealth,

poverty, their social rank and became "warriors" risking their lives to

help and save others from the horror of war. While they did not sign

up for the role, they performed it gloriously, many risking their lives to

help the less able out of the burning World Trade Center. Some even

gave their lives so others could live.

We Were Soldiers was a movie about

courage, not about war.

I abhor most modern war movies for the

simple reason they are laced with acrid contempt for the truth. They

riddle the script with attacks on corrupt military or political ideals

twisting the true story into a gagging array of scenes that make the

viewer think only of the horror, not the glorious moments, when men put

their lives on the line for others. It has been said that until a

man is willing to die for something, he never knows life's true meaning,

he never puts his soul on the line. The same goes for women.

That's why I loved the napalm.

It rose up on the screen to level the overwhelming odds of over

3,000 North Vietnamese versus 450 American warriors in the first major

battle of the Vietnam War. So many times in my own experience

the napalm had come to save us from destruction when our units were

trapped by the enemy, when men were dying next to me, their blood

splattering on my face. Then, out of the clear blue sky it rose,

flashing heat that boiled the earth, giving us time to regroup, to prepare

for the next stage.

Then there was blood. It was real. I

knew the movie was more than Hollywood when I saw it. When the medical evacuation choppers shuttled the dead and wounded back, I leaned

over to my wife and said..."They don't need to lift them out of the

chopper, the blood is so thick they slide out." Just as I whispered

those words to my wife the scene on the screen showed a soldier dumping a

bucket of water on the floor of the chopper, washing the blood off the

deck. I watched it drip out, my mind whisked back thirty-five years

earlier when I clambered aboard choppers so slick with blood I was afraid

I would slide out as we lifted off.

medical evacuation choppers shuttled the dead and wounded back, I leaned

over to my wife and said..."They don't need to lift them out of the

chopper, the blood is so thick they slide out." Just as I whispered

those words to my wife the scene on the screen showed a soldier dumping a

bucket of water on the floor of the chopper, washing the blood off the

deck. I watched it drip out, my mind whisked back thirty-five years

earlier when I clambered aboard choppers so slick with blood I was afraid

I would slide out as we lifted off.

Like so other would-be warriors, I had joined the

Marine Corps to learn to be a man, not to become a war correspondent.

The Marine Corps made that decision and assignment for me. I

wanted to be a warrior with the best of warriors. Fortunately, I

served under a man so much like Mel Gibson's Lt. Colonel Moore character

(see actual picture of Lt. Colonel Moore) it was frightening. My

"Mel Gibson" was a man named Leon Utter, commander of the 2nd Battalion,

7th Marines. Like Gibson's character, we prayed before battle.

Utter told us about the glory of dying for our cause. He was the

first in and the last out. He stood and gave commands when bullets

hailed at us as thick as swarms of angry hornets, more concerned with

leadership than safety.

Men died for him, not for flag or country or Corps.

He inspired leadership, fueled one's courage in the face of certain death

and limitless mountains of fear.

There were other revelations for me in the movie.

One was UPI Joe Galloway. (see picture on left of him

with camera and weapon)

I saw

myself as him--a man who captured the battle not only with pictures, but

with words. In a way, he was me--torn between being a

"non-combatant" and a "reporter." There were times in Vietnam

when I was so disenfranchised from the battle that all I could see was

pictures, and other times when all I could see was the end of my sight on

my M-16 and the muzzle blast. Fighting a war and recording it

simultaneously is hard work. Eventually, the reporter became a

warrior, just as the warrior in me finally became a reporter.

It is one thing to take a picture of blood, it is another thing to create

it. Both ultimately merge into one. I saw

myself as him--a man who captured the battle not only with pictures, but

with words. In a way, he was me--torn between being a

"non-combatant" and a "reporter." There were times in Vietnam

when I was so disenfranchised from the battle that all I could see was

pictures, and other times when all I could see was the end of my sight on

my M-16 and the muzzle blast. Fighting a war and recording it

simultaneously is hard work. Eventually, the reporter became a

warrior, just as the warrior in me finally became a reporter.

It is one thing to take a picture of blood, it is another thing to create

it. Both ultimately merge into one.

Joe Galloway may be chided by some for picking up arms,

when the role of the journalist is to be independent. But as

Sam Elliot, who played tough Sergeant Major Basil Plumly said when he told

Joe to get a gun, "there are no noncombatants today." Joe was

awarded the Bronze Star for bravery by the U.S. Army in 1998, a

retroactive award to when he helped save many lives at his own risk.

"There are no non-combatants in war."

Whether we agree or disagree, we know when that moment arrives that we

must "fight or die." On September 11th, the people who were

caught in the hell of the attack know this truth. As I stood

and watched the buildings collapse and the debris shot at us, there was no

difference between observer and participant. We all faced death.

Some survived, others didn't.

While I cannot, and would not promote that

Vigilance is about carrying a gun or dying for a cause, I will firmly say

that Vigilance requires Courage over Fear, Conviction over Intimidation,

and Action over Complacency.

In the movie, both the North Vietnamese and the

Americans were equal in expressing theirs. I found that

powerful.

On September 11th the resolve of innocent Americans to

fight against incredible odds of death and destruction were also heroic.

The fact that over 20,000 people escaped death that day is a tribute to

acts of courage that far surpass those of the fire and police and

emergency workers on the scene. I continually remind my

readers that the overlooked heroes of that day, the people not put up on

posters around the city, the faces not plastered on 42nd Street

billboards, the lavish honors not reaped go to the thousands of

"grunts"--the civilians inside the building and outside, the men and women

not trained to fight to save another, but who fought to save others.

Not that I diminish the acts of heroism by a fireman or

policeman who rushes into a burning building, but rather I know the real

heroes, the unsung, were those men and women who stopped to help or save

another human being not because they were "on duty to do so," but because

they had a innate "duty to do so."

The North Vietnamese and American Soldiers had innate

duties to die for their causes. This was so brilliantly expressed by

the scene in the movie of the North Vietnamese administrative solider who

wore glasses and wrote in his diary to his wife and then sucked up the

courage to attack, almost bayoneting the Mel Gibson character. It

was touching that the diary was sent to his loved one, a symbol of honor

among warriors.

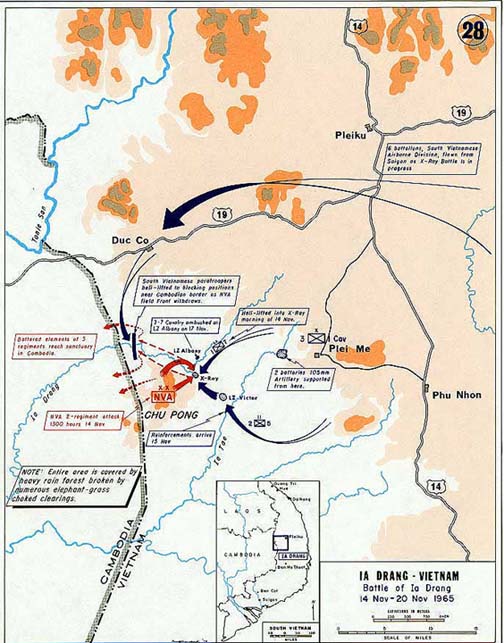

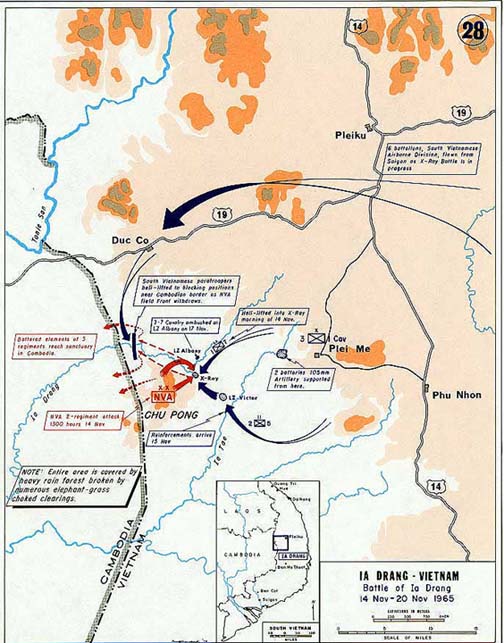

As I researched my feelings about this movie, I came

across a story about one of the men who was a vital part of the battle of

November 14-17, 1965 in the Ia Drang Valley. He performed many

heroic acts that day.

On September 11, three and a half decades later, he

also performed heroic acts saving hundreds of lives in the World Trade

Center attack. I haven't seen his picture on any posters around New

York City, but he should be among them. Below, I have

reprinted part of the story of his heroism. I provide a link to the

rest of the story for readers who want to know more about the courage,

conviction and action a person takes in time of crisis.

There are many more like him. We might never know

all their stories. But they are, what I call, the Sentinels of

Vigilance--a composite of human courage that stands above the battlefield

of the World Trade Center, men and women, mothers, fathers, grandparents,

cousins, nephews, nieces, uncles and aunts--who, as bravely as the 1,800

North Vietnamese who died in battle or Americans in the Ia Drang Valley,

deserve the title: "We Were Soldiers!"

"We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he today

that sheds his blood with

me Shall be my brother." (Shakespeare, Henry V, Act IV, Scene 3).

Partial Reprint of Story--on Rick Rescorla--

A Tower of

Courage

On September 11, Rick Rescorla Died as

He Lived: Like a Hero

By Michael Grunwald

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, October 28, 2001; Page F01

NEW YORK

"You watching TV?"

Rick Rescorla was calling from the 44th floor of the World Trade

Center, icy calm in the crisis. When Rescorla was a platoon leader

in Vietnam, his men called him Hard Core, because they had never

seen anyone so absurdly unflappable in the face of death. Now he was

vice president for corporate security at Morgan Stanley Dean Witter

& Co., and a jumbo jet had just plowed into the north tower. The

Voices of officialdom were crackling over the loudspeakers in the

south tower, urging everyone to stay put: Please do not leave the

building. This area is secure. Rescorla was ignoring them.

"The dumb sons of bitches told me not to evacuate," he said

during a quick call to his best friend, Dan Hill, who had indeed

been watching the disaster unfolding on TV. "They said it's just

Building One. I told them I'm getting my people the [expletive] out

of here."

Keep moving, Rescorla commanded over his megaphone while Hill

listened. Keep moving.

"Typical Rescorla," Hill recalls. "Incredible under fire."

Morgan Stanley lost only six of its 2,700 employees in the south

tower on Sept. 11, an isolated miracle amid the carnage. And company

officials say Rescorla deserves most of the credit. He drew up the

evacuation plan. He hustled his colleagues to safety. And then he

apparently went back into the inferno to search for stragglers. He

was the last man out of the south tower after the World Trade Center

bombing in 1993, and no one seems to doubt that he would've been

again last month if the skyscraper hadn't collapsed on him first.

One of the company's secretaries actually snapped a photo of

Rescorla with his megaphone that day, a 62-year-old mountain of a

man coolly sacrificing his life for others.

It was an epic death, one of those inspirational hero-tales that

have sprouted like wildflowers from the Twin Towers rubble. But it

turns out that retired Army Col. Cyril Richard Rescorla led an epic

life as well. In this time when heroes are being proclaimed all

around, when brave actions are understandably hailed as proofs of

character, here was a man whose heroism was a matter of public

record long before Sept. 11.

At the same time, Rescorla's own fascination with heroism and

hero-tales was a matter of private record. He even co-wrote a

screenplay about the World War II infantry legend Audie Murphy.

Rescorla was a man of introspection as well as action, and some of

his final soul-searching e-mails provide an eerie commentary on his

final day.

Rescorla, after all, was once an infantryman himself, declared a

"battlefield legend" in the 1992 bestseller "We Were Soldiers Once .

. . and Young." Another photo of Rescorla -- gaunt back then,

unshaven, carrying his M-16 rifle with bayonet fixed -- graced the

book's cover and became an enduring image of the Vietnam War.

The survivors of the 7th Cavalry still tell awestruck stories

about Rescorla. Like the time he stumbled into a hooch full of enemy

soldiers on a reconnaissance patrol in Bon Song. Oh, pardon me, he

said, before firing a few rounds and racing away.

"Oh comma pardon me," repeats Dennis Deal, who followed Rescorla

that day in April 1966. "Like he had walked into a ladies' tea

party."

Or the time a deranged private pulled a .45-caliber pistol on an

officer while Rescorla was nearby, sharpening his bowie knife. "Rick

just walked right between them and said: Put. Down. The. Gun,"

recalls Bill Lund, who served with Rescorla in Vietnam. "And the guy

did. Then Rick went back to his knife. He was flat out the bravest

man any of us ever knew."

Rescorla was also a passionate and complex man, a writer and a

lawyer, as well as a blood-streaked warrior and six-figure security

expert. At his home in suburban Morristown, N.J., he carved wooden

ducks, frequented craft fairs, took playwriting classes. He wrote

romantic poetry to his second wife, Susan, and renewed their vows

after just one year of marriage. "He was a song-and-dance man," she

says. He was a weeper, too. He liked to quote Shakespeare and

Tennyson and Byron -- and Elvis and Burt Lancaster. He was a film

buff, history buff, pottery buff -- "pretty much any kind of buff

you can be," says his daughter, Kim. He liked to point his Lincoln

Mark VIII in random directions and see where it would take him.

In his last days, Rescorla had been reading up on Zen Buddhism

and the Stoics, contemplating the directions his own life had taken

him. A few years ago, he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer

that had spread into his bones. His doctors had given him six months

to live. But the cancer was in remission, and he couldn't help but

wonder what it all meant. In a Sept. 5 e-mail to his old friend Bill

Shucart -- once a medic in Vietnam, now the head of neurosurgery at

a Boston hospital -- he mused about kairos, a Greek word for a

cosmically meaningful moment outside of linear time.

"I have accepted the fact that there will never be a kairos

moment for me, just an uneventful Miltonian plow-the-fields

discipline . . . a few more cups of mocha grande at Starbucks, each

one losing a little bit more of its flavor," he wrote.

But Rescorla's moment was coming soon.

'A Natural Number One Man'

This American story began in England.

|

Go To Mar.

3 "Vigilance And The Street Bum"

©2001

- 2004, VigilanceVoice.com, All rights reserved - a ((HYYPE))

design

|

|

I was glued to my seat, reliving the past in Randall Wallace's brilliantly

directed We Were Soldiers, a movie from my viewpoint about the

grueling test of men fighting to the death not for God or Country but for

themselves--warriors fighting for the glory of their own survival.

I was glued to my seat, reliving the past in Randall Wallace's brilliantly

directed We Were Soldiers, a movie from my viewpoint about the

grueling test of men fighting to the death not for God or Country but for

themselves--warriors fighting for the glory of their own survival.

medical evacuation choppers shuttled the dead and wounded back, I leaned

over to my wife and said..."They don't need to lift them out of the

chopper, the blood is so thick they slide out." Just as I whispered

those words to my wife the scene on the screen showed a soldier dumping a

bucket of water on the floor of the chopper, washing the blood off the

deck. I watched it drip out, my mind whisked back thirty-five years

earlier when I clambered aboard choppers so slick with blood I was afraid

I would slide out as we lifted off.

medical evacuation choppers shuttled the dead and wounded back, I leaned

over to my wife and said..."They don't need to lift them out of the

chopper, the blood is so thick they slide out." Just as I whispered

those words to my wife the scene on the screen showed a soldier dumping a

bucket of water on the floor of the chopper, washing the blood off the

deck. I watched it drip out, my mind whisked back thirty-five years

earlier when I clambered aboard choppers so slick with blood I was afraid

I would slide out as we lifted off. I saw

myself as him--a man who captured the battle not only with pictures, but

with words. In a way, he was me--torn between being a

"non-combatant" and a "reporter." There were times in Vietnam

when I was so disenfranchised from the battle that all I could see was

pictures, and other times when all I could see was the end of my sight on

my M-16 and the muzzle blast. Fighting a war and recording it

simultaneously is hard work. Eventually, the reporter became a

warrior, just as the warrior in me finally became a reporter.

It is one thing to take a picture of blood, it is another thing to create

it. Both ultimately merge into one.

I saw

myself as him--a man who captured the battle not only with pictures, but

with words. In a way, he was me--torn between being a

"non-combatant" and a "reporter." There were times in Vietnam

when I was so disenfranchised from the battle that all I could see was

pictures, and other times when all I could see was the end of my sight on

my M-16 and the muzzle blast. Fighting a war and recording it

simultaneously is hard work. Eventually, the reporter became a

warrior, just as the warrior in me finally became a reporter.

It is one thing to take a picture of blood, it is another thing to create

it. Both ultimately merge into one.