The

VigilanceVoice

The

VigilanceVoice

VigilanceVoice.com

vv

Thursday--

May 16, 2002—Ground

Zero Plus 247

Emergency Room--Hall Of Terror

by

Cliff McKenzie

Editor, New York City Combat Correspondent News

GROUND ZERO, New York City, May 16--I don't watch the

Emmy-winning show, ER. One of the reasons is I didn't

believe the constant madness and crisis was real.

I have changed my viewpoint. Terrorism lives in the Emergency

Room at Saint Vincent's Hospital in New York City. I was

its witness. I affirm its madness.

I was en route to

Ground Zero for my "Crisis of Ordination" confrontation

yesterday morning with my sister and wife. I had

insisted on taking along a wheel chair for my sister, who suffers

from a multitude of leg and ankle problems. I was being

a Sentinel of Vigilance, ready to protect her weak ankles and

legs from the grueling, pounding assault of New York City sidewalks

when it happened.

As I was lifting the wheel

chair, a sharp, nauseating pain rocketed through my chest and

side. I felt the punji-tipped pain spears sinking

deep into my ribs. I gasped. I hoped it would pass

and we began to walk toward Ground Zero. Each step I took

increased the pain until I had to stop.

"I have to go to the Emergency Room," I said, holding

on to the side of the wheel chair, my breath short, angry that

my sister's first day of visiting in New York City from Las

Vegas was being spoiled by my sudden painful attack.

"I have to go to the Emergency Room," I said, holding

on to the side of the wheel chair, my breath short, angry that

my sister's first day of visiting in New York City from Las

Vegas was being spoiled by my sudden painful attack.

We took the wheel chair

back to the apartment and climbed in a cab, directing it to

go to Saint Vincent's Hospital. I tried to joke with my

Haitian cab driver who had commented about his own back problems

as I gasped and groaned my way into the cab..

"I was born in March,

a Capricorn," he said in a heavy accent. "I

have much bad luck in my life." When

I asked what was the worst thing that happened, he told me that

he was one day late in payment on his business and the bank

foreclosed, stripping him of his livelihood. Even

though I was in pain, I thought how painful it would be to live

in a country where the rights of the citizens were subject to

losing one's vocation over a 24-hour-default.

"I wish you more good

than bad luck," I said, exiting the cab, trying to keep

my mind off the excruciating pain stabbing at my chest and side

as I moved toward the ER door, assisted by wife and sister.

Everything went orderly,

normal at first.

The waiting room was about

a quarter filled. Some were moaning. One guy had

a patch over his eye, but otherwise it appeared a regular, simple

day of emergency treatment.

A few months earlier I

had been to the ER at Beth Israel with my daughter and her daughter

and knew the drill of waiting and waiting, so I was prepared.

I had my carving tools and a piece of wood with me, but had

no desire to do anything than wait in pain for the relief the

doctors would give me through X-raying and examining me to assure

I hadn't done any permanent damage. At 6-4 and 270 pounds,

the last thing I wanted was a slipped disc. I was hoping

for a stripped and injured muscle.

I signed the admission

documents. I didn't read them. I can't imagine anyone

in an ER state-of-mind taking a microscope to what the words

said. I was lucky to scrawl my name. They

attached a wristband with my name and hospital serial number,

my "Band Of ER Courage," and I waited for my name

to be called.

Security at hospitals in

New York is like Fort Knox. Tall, tough-looking

guards in green jackets and sour-expressions guard the doors.

There are buzzers and codes on them that have to be punched

in. No cell phones are allowed.

I thought it ironic that

hospitals have more security than airports. It seemed

a far stretch to imagine a Terrorist walking into an ER with

a bomb strapped to his or her chest, but then I was about to

learn why that was a major possibility.

My name was finally called

and I was given security entrance to the bowels of the ER.

Chairs lined the wall where patients sat, and hospital gurneys

were butted up at one end of the chairs with patients lying

on them, some babbling to themselves others reading a newspaper,

some just staring blankly at the ceiling.

A young woman, a Physicians

Assistant, examined me. She checked my back for

disc pain and took my history, then told me they would give

me a shot for the pain and take X-rays. She told

me to wait.

I was sitting on a chair

in the ER room. A woman next to me was telling a social

worker about how she was beaten by her husband. Another

woman across the way was bleeding from her nose, some after-effect

of an operation. Blood stained her blouse and she pressed

a huge icepack against her nose. Next to me, on

my left, an older black woman who was blind had a huge lump

protruding from her jaw, a blocked sebaceous gland, the PA said.

I could see it throbbing on her jaw, as though she had a huge

wad of cotton stuffed in her mouth. Her husband stood

Vigilantly with her.

I sat there for over an

hour. I listened to the madness and disorder of the room.

Nurses yelling at one another. Doctors arguing.

It seemed every member of the staff was mad, in conflict with

one another. It wasn't like the movies or

TV. programs where everyone is harmonized in the madness of

the moment, all for one and one for all. This seemed to

be "every-man-for-himself" management.

Unable to find any pain reliever

medication for me as they fished through a drawer,

they told me to go get my X-Rays. An older woman

led me down the cluttered hall.  Another nurse told her to tie my hospital robe and they had

a huge argument over who was in charge of me. I stood

there between them, wondering if this was a joke or for real.

It was for real.

Another nurse told her to tie my hospital robe and they had

a huge argument over who was in charge of me. I stood

there between them, wondering if this was a joke or for real.

It was for real.

"She's always trying to

tell me my job," the woman told me. "I've worked

here for thirty years, what does she know."

I didn't respond. I shuffled

slowly, painfully toward the elevator.

Again, I waited upstairs for

someone to come get me for an X-Ray. It seemed I

was invisible. Finally my name was called and I

groaned and grimaced and made my way behind the large, hulking

shaped Jamaican woman who was my X-Ray tech. She limped

as she walked, and I wondered if she had been afflicted with

what I had for she seemed to be in more pain than I. I

said nothing. Jokes seemed inappropriate.

Because of my size, they cross

X-rayed me. I stood for a series of X-rays of my

front and side, and then they had me lie on a table and began

to take a series of additional pictures. Each time

I moved the pain shot through me. I could hear people

laughing and joking and telling stories about their lives in

the adjoining film processing room. It seemed that

patients were flies on the walls, interposing themselves between

the lives of the staff, necessary evils to their existence and

conversations.

I was told to wait for

someone to take me back down to the ER. My X-ray

tech shouted to the people at the desk who were talking to one

another that I needed an escort. They said nothing.

I sat for about a half an hour, just about ready to waddle myself

to the elevator and go down to the ER solo when someone came

by and was told I needed to go back to the ER. I was worried

because my X-rays hadn't been read yet. It was nearly

2 p.m. and I had arrived at the ER at 11:00 a.m.

The ER was filled with people

when I returned. There was one chair left. I eased

myself down and leaned back against the wall.  The

sounds of moans served as a chorus to the shouts and barking

of the nurses and doctors working on people. I tried

not to pay attention to the chaos. I just wanted my X-rays

read, a prescription for the pain, and to leave.

The

sounds of moans served as a chorus to the shouts and barking

of the nurses and doctors working on people. I tried

not to pay attention to the chaos. I just wanted my X-rays

read, a prescription for the pain, and to leave.

Then all hell broke loose.

First, two Port Authority cops

entered with a prisoner to get him treatment. He had a

black eye and appeared to bleeding from the head.

He was a huge guy, with thick shoulders and a barrel chest.

The two cops were small and slight. I figured the prisoner

could take them both with one punch.

Up to that point I assumed the

ER stories on television and the movies were manufactured drama.

The hallway had been quiet, almost sedate. But now

the reality of madness was unfolding.

Inside the treatment room a man

started cursing the nurses and doctors, refusing to take off

his shirt, yelling the "F"-word at everyone and demanding

to be released, to exit. Four security guards rushed

into the room. .jpg) A confrontation was growing. I was going to stand and

peer inside but decided if there was a scuffle I might get bowled

over, and add to my injury. So I just listened as the

guards refused to let the man leave and told him they would

strip him if he didn't do it himself.

A confrontation was growing. I was going to stand and

peer inside but decided if there was a scuffle I might get bowled

over, and add to my injury. So I just listened as the

guards refused to let the man leave and told him they would

strip him if he didn't do it himself.

I was perplexed.

It was as though I were in a jail, and all individual rights

had been left at the security door. Part of me wanted

to jump up to the man's defense, but I bit my tongue.

The pain and need for relief overpowered by righteous indignation.

More people poured into the narrow

hallway. A tall, lanky woman, perhaps in her twenties

or early thirties stood bobbing her head, intermittently laughing

and then twitching and grumbling. She was pale and

pasty, appearing like a drug addict coming down. Her sister

accompanied her, trying to soothe her. She was given

hospital gowns and told to remove her clothes and wait to be

called.

She and her sister found a seat

next to me. I overhead her conversations with her sister.

She was complaining about the long wait, bobbing in and out

of hysterical laughs and depressive anger. She kept

insisting she wanted a cigarette and finally pulled one out.

I thought she was going to light up right there. She kept

saying the "F" word in relation to the hospital, the

staff and the long, grueling wait. Finally she bolted

from her chair and rushed out the security door to the entrance

where she could smoke. A doctor yelled at the security

guards, all of whom were crowded around the man who wouldn't

take off his shirt, that a patient was outside smoking.

Two guards rushed out the

security doors. The girl was forced back inside.

She told the guards to keep their hands off her and began to

scream and kick and swing her fists at them, yelling she wanted

to leave, to get the "F" out of there.

Four guards tried to restrain

her. She thrashed at them, screaming madly at the top

of her lungs. A nurse rushed out with a syringe and long

needle and injected her with some tranquilizing drug.

The girl slumped into a rag doll and was dragged back to her

seat next to her sister, next to me, her head lolling.

It wasn't over yet.

The calm had brewed into a storm, far beyond anything I had

seen on television or the movies, far more real than fiction

could paint.

Against the wall stood a young

Hispanic woman with her mother. The woman's hands were

all twisted into a deformed claw and her fingers twisted and

twitched as she stared vacantly about, seemingly unaware of

the cacophony around her.

The sister sitting next to me

stood up. The nurse told the young Hispanic woman to sit

down. Her mother was pressed up against the wall, standing,

quietly assuming the position of wallpaper. I stood and

offered the mother my chair next to her daughter. She

graciously accepted.

It was nearing 3 p.m., five hours

since I had arrived. I wanted the PA to see me, hoping

she would read my X-rays and let me leave the Snake pit the

hall had become.

Then Nurse Ratchet, or one that

looked like the infamous nurse from One Flew Over The Cuckoo

Nest, appeared.  She began to tell other nurses about the paranoid schizophrenic

patients in the hall. She spoke in a loud, coarse Voice,

as though the patients were suspended in time, talking about

each one and pointing at them as she warned the other nurses

to "keep an eye on them." One she singled out

was the young Hispanic girl with the twitching, twisted hand

and vacantly frightened stare just three feet away from her.

I wondered about the ethics of demeaning patients' conditions

in front of them and other patients. I wondered about

the Terror the alleged "angels of mercy" were injecting

into the mind of the young girl, shoveling more trauma on an

already disturbed soul.

She began to tell other nurses about the paranoid schizophrenic

patients in the hall. She spoke in a loud, coarse Voice,

as though the patients were suspended in time, talking about

each one and pointing at them as she warned the other nurses

to "keep an eye on them." One she singled out

was the young Hispanic girl with the twitching, twisted hand

and vacantly frightened stare just three feet away from her.

I wondered about the ethics of demeaning patients' conditions

in front of them and other patients. I wondered about

the Terror the alleged "angels of mercy" were injecting

into the mind of the young girl, shoveling more trauma on an

already disturbed soul.

Later, I was to learn her

hands were the result of too many psychotropic drugs, a common

condition for those who live a drugged existence to counterbalance

their terror.

Then the young black man

a few seats to my left yelled at the security guards to let

the "F"-ing man who didn't want to take his shirt

off leave. He began to yell at all the ER staff,

especially Nurse Ratchet who told him to not use that kind of

language.

He was a well dressed,

educated young man who was exasperated. He began to tell

Nurse Ratchet how disorganized and confused the management of

the ER room was.

Taking umbrage, Nurse Ratchet

began to defend the ER, and told the man that his attitude was

not the kind of attitude that would get him treated in a timely

fashion. He retorted that he had been there for five hours,

and had a lacerated eye, and no one had seen him yet and that

he was pissed.

Then he pulled out his

cell phone--a violation--and dialed a number. Nurse Ratchet

called security. The guards rushed at the young man.

"I'm calling the local television station to come down

here and film this insanity," the man said. "This

is madness."

The security guards

started to take the phone away and the young man closed it and

stuck it in his pocket. Nurse Ratchet told the young man

to stop yelling, which he wasn't, and that if he wanted to be

treated he would be nicer.

I wanted to vomit.

But, more importantly, I wanted to leave.

Next to the young

man was an older woman with Alzheimer's Disease, accompanied

by her friend. The older woman was disoriented.

They had been waiting for over four hours. The older woman's companion had had enough. She took her

ailing, fragile friend by the hand and tried to coax her up

and out.

The older woman's companion had had enough. She took her

ailing, fragile friend by the hand and tried to coax her up

and out.

"We have to

leave," her friend said. "They are too busy

here. We are not waiting any longer."

"But...but...I

want to stay," the older lady cried..."I don't want

to go...I want help..."

"They can't help you

here...they are too busy..." her companion said, her Voice

frustrated, the idea of sitting there for hours upon hours more

oppressive than the trauma of leaving.

Finally, my PA appeared

with my X-rays. She put them up on the viewer and

I began to ask her questions and then realized she wasn't a

doctor, and was probably not yet thirty. I realized

the insanity of me expecting her to know details of my problem,

or to read the picture of my lungs. I still smoke, and

wanted the X-rays for a look at my damage, if any, as well as

the signs of torn ligaments and muscles.

I choked off my questions.

Took my prescriptions and left. I glanced back at the

room before I exited the security doors, at the rows of people

waiting, at the young Hispanic woman's hands twitching, at the

black man's angry face and lacerated eye, at the lolling head

of the woman who had been tranquilized, at the security guards

lingering near the treatment door where the man who refused

to take off his shirt still threatened to erupt.

That evening I told the story

to my wife. As a hematologist, she had worked in many

ER situations. I was perplexed at the militaristic

stripping of people's rights in the ER room, and told her about

my siding with the patients who abhorred the treatment of the

other patients.

"That release you signed,

Cliff, remember it?" she queried.

"Yes."

"It gives the hospital total

rights over your body. When you enter an ER, you give

up personal rights.  You

go under their command, control. It's like you enter

there for help, and when the help is offered and you resist,

you lose the right of choice. Lots of people walk into

an ER and then fight the treatment. So hospitals protect

themselves. They assume you want help or you wouldn't

sign a release."

You

go under their command, control. It's like you enter

there for help, and when the help is offered and you resist,

you lose the right of choice. Lots of people walk into

an ER and then fight the treatment. So hospitals protect

themselves. They assume you want help or you wouldn't

sign a release."

I thought about it.

It made sense. But it didn't make sense.

Years ago my wife had been knocked

out by a patient she was drawing blood from--a sheriff who was

unconscious and when he awoke to a needle in his arm--slugged

my wife and knocked her across the ER room. It was reflex,

not intentional.

Still, it seemed I had been in

a Hall of Terror. It seemed to me the rights of

command over the patients had been exaggerated at their expense.

I saw no justification

for the way in which those people were treated, especially the

authoritarian Terrorist attitude taken by the employees.

But this was a Triage treatment center, in the heart of New

York City. What did I expect.

Still, I thought especially

of the young Hispanic woman with the deformed fingers.

I thought of her being driven deeper into her dark inner sanctum

by the "angels of Terror" who spoke about her in such

demeaning terms.

On the obverse, I thought

of the Alzheimer's patient and her companion, who quietly sat

for hours--two old ladies seeking solace--in a world that paid

no heed to them, and gave them no solace for their pain.

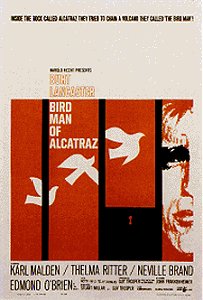

As I left with my sister

I took a deep breath outside. I felt like the Birdman

of Alcatraz who stepped out of the cold walls of a prison in

which all my rights had been exsanguinated, into the warmth

of freedom.

"How'd it go,"

my sister asked.

"I'll tell you later,"

I replied. "Right now I want to smell freedom."

G0

TO: May 15--Crisis of Ordination

"I have to go to the Emergency Room," I said, holding

on to the side of the wheel chair, my breath short, angry that

my sister's first day of visiting in New York City from Las

Vegas was being spoiled by my sudden painful attack.

"I have to go to the Emergency Room," I said, holding

on to the side of the wheel chair, my breath short, angry that

my sister's first day of visiting in New York City from Las

Vegas was being spoiled by my sudden painful attack.

Another nurse told her to tie my hospital robe and they had

a huge argument over who was in charge of me. I stood

there between them, wondering if this was a joke or for real.

It was for real.

Another nurse told her to tie my hospital robe and they had

a huge argument over who was in charge of me. I stood

there between them, wondering if this was a joke or for real.

It was for real. The

sounds of moans served as a chorus to the shouts and barking

of the nurses and doctors working on people. I tried

not to pay attention to the chaos. I just wanted my X-rays

read, a prescription for the pain, and to leave.

The

sounds of moans served as a chorus to the shouts and barking

of the nurses and doctors working on people. I tried

not to pay attention to the chaos. I just wanted my X-rays

read, a prescription for the pain, and to leave..jpg) A confrontation was growing. I was going to stand and

peer inside but decided if there was a scuffle I might get bowled

over, and add to my injury. So I just listened as the

guards refused to let the man leave and told him they would

strip him if he didn't do it himself.

A confrontation was growing. I was going to stand and

peer inside but decided if there was a scuffle I might get bowled

over, and add to my injury. So I just listened as the

guards refused to let the man leave and told him they would

strip him if he didn't do it himself. She began to tell other nurses about the paranoid schizophrenic

patients in the hall. She spoke in a loud, coarse Voice,

as though the patients were suspended in time, talking about

each one and pointing at them as she warned the other nurses

to "keep an eye on them." One she singled out

was the young Hispanic girl with the twitching, twisted hand

and vacantly frightened stare just three feet away from her.

I wondered about the ethics of demeaning patients' conditions

in front of them and other patients. I wondered about

the Terror the alleged "angels of mercy" were injecting

into the mind of the young girl, shoveling more trauma on an

already disturbed soul.

She began to tell other nurses about the paranoid schizophrenic

patients in the hall. She spoke in a loud, coarse Voice,

as though the patients were suspended in time, talking about

each one and pointing at them as she warned the other nurses

to "keep an eye on them." One she singled out

was the young Hispanic girl with the twitching, twisted hand

and vacantly frightened stare just three feet away from her.

I wondered about the ethics of demeaning patients' conditions

in front of them and other patients. I wondered about

the Terror the alleged "angels of mercy" were injecting

into the mind of the young girl, shoveling more trauma on an

already disturbed soul.

The older woman's companion had had enough. She took her

ailing, fragile friend by the hand and tried to coax her up

and out.

The older woman's companion had had enough. She took her

ailing, fragile friend by the hand and tried to coax her up

and out. You

go under their command, control. It's like you enter

there for help, and when the help is offered and you resist,

you lose the right of choice. Lots of people walk into

an ER and then fight the treatment. So hospitals protect

themselves. They assume you want help or you wouldn't

sign a release."

You

go under their command, control. It's like you enter

there for help, and when the help is offered and you resist,

you lose the right of choice. Lots of people walk into

an ER and then fight the treatment. So hospitals protect

themselves. They assume you want help or you wouldn't

sign a release."