The

VigilanceVoice

The

VigilanceVoice

VigilanceVoice.com

Saturday-- June 8,

2002—Ground Zero Plus 269

Blood On A Leaf

by

Cliff McKenzie

Editor, New York City Combat Correspondent News

GROUND ZERO, New York City,

June 8--The story in the New York Times this morning about

construction workers at Ground Zero finding a new cache of body parts in a

building adjacent to the World Trade Center startled me.

On May 30, I walked in tribute at the Ground Zero

closing ceremonies with the families of those who had been confirmed dead

or missing during the September 11th Terrorist attack

Officially, the search and rescue

operations ended that day.

Symbolically, the last "body" was carried out of the Ground Zero pit to

sound of Taps, put in an ambulance and driven slowly up West Street

through an honor guard of firemen, police and rescue workers who, for the

past nearly nine months, had dug and raked through millions of tons of

dirt and debris to find any remaining signs of the missing.

Symbolically, the last "body" was carried out of the Ground Zero pit to

sound of Taps, put in an ambulance and driven slowly up West Street

through an honor guard of firemen, police and rescue workers who, for the

past nearly nine months, had dug and raked through millions of tons of

dirt and debris to find any remaining signs of the missing.

Of the 2823 people presumed confirmed dead

in the attack, only 1,058 have been identified as of May 30. I

thought perhaps the ceremony might offer me some closure, some suturing of

the wounds of that horrible day when I witnessed bodies leaping from

windows, and shuddered as the buildings collapsed and washed us all in a

deathly pall I was sure contained bio-chemical agents.

I hoped the ceremonies would end my constant reminder

of the devastation of war. The door to my memories of Vietnam

had never been shut. I thought participating in closure ceremonies

on May 30 might offer some reprieve from both old and new war scars.

I was wrong.

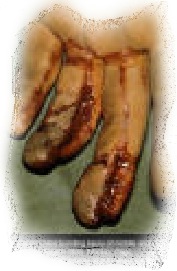

This morning's Times article talked about finding fingers in the

building's rain gutter, and jaw bones with teeth intact in the guts of

building. The body parts were found in a bank building adjacent to

the World Trade Center. It hadn't been searched because primary

attention was given to Ground Zero soil. After rescue operations

ceased, construction workers began to dismantle the wounded building.

Inside, they found found parts of the airplane--seats and baggage

containers--as well as human remains scattered everywhere.

This morning's Times article talked about finding fingers in the

building's rain gutter, and jaw bones with teeth intact in the guts of

building. The body parts were found in a bank building adjacent to

the World Trade Center. It hadn't been searched because primary

attention was given to Ground Zero soil. After rescue operations

ceased, construction workers began to dismantle the wounded building.

Inside, they found found parts of the airplane--seats and baggage

containers--as well as human remains scattered everywhere.

My stomach turned as I read the story.

It was like Promethius opening Pandora's Box again. I saw the horror of

the past come to life. This time it was more vivid, more

disturbing because my Vigilance guard was down. After May 30, I

lowered my emotional shields. I cried that day when Taps was

played. I had never cried before for war victims, or my part in war. I

did that day.

The Times story sobered me to the reality that death

and destruction always lingers, constantly fertilizes the present with its

acrid scent of decaying flesh locked in my memory cells. I had hoped

the Closing Ceremonies washed such memories clean.

But the article resurrected the stench within.

It triggered ancient memories of Terrorism I

prefer not to embrace. They were of a time three-and-a-half

decades ago when I was a young warrior in the Marine Corps,

marching

through the rice paddies of Vietnam on one of many "search and

destroy" missions.

marching

through the rice paddies of Vietnam on one of many "search and

destroy" missions.

It brought back the vivid memory of a bloody leaf.

In early 1966 we were hunting

North Vietnamese regulars--the toughest of all enemies one could face in

Vietnam. They were regimented warriors, not hit-and-run specialists

like the Viet Cong. They stood their ground and fought to the death,

taking as many of us with them as possible.

They ambushed us, pinning us down in a rice

paddy. We crawled into our helmets, using any tiny precipice of a paddy dike

for cover, waiting to die as the crossfire laced a network of lead inches

above our heads and making it impossible to assault without instantly being

cut in half.

We lay in the muck and lifted our rifles up

blindly and fired, not daring to raise our heads into the killing zone to

take aim. We radioed for air support, hoping our Marine close air

support would swoop down and surgically drop napalm or bombs on the enemy

and not us. The North Vietnamese were so close you could smell the foul

odor of their fish oil saturating the bags of rice they feasted upon so

they could kill us on full stomachs.

Finally, the planes screamed down. The heat of the napalm scorched us. We buried our faces in the dirty paddy

water praying the jet jockeys didn't miss their targets and light us up.

Then we assaulted.

The heat of the napalm scorched us. We buried our faces in the dirty paddy

water praying the jet jockeys didn't miss their targets and light us up.

Then we assaulted.

A few of the Vietnamese warriors survived. They

injected themselves with heroin or opium, and tied their hands to the

grips of their machine guns. Some were literally cut in half but

still firing, the drug easing the pain of death as their fingers twitched

on the triggers, taking as many of us out before the final drops of their

blood drained into the soil.

In the end it wasn't a victory. No one cheered as

we waded through the charred bodies, searching for any lingering life,

wary of snipers tied into trees. The snipers protected the

retreating enemy. They tied themselves to the trees so if they were wounded they wouldn't

fall and could squeeze off final rounds before we blew the tree and their

remaining bodies to kingdom come. They died honorable warriors.

Some battles end in reverent silence. When

warriors fight fiercely to the death it seems there is no jubilation on

the victor's side--just a gladness it is over prevails--an ecclesiastical resignation to

the end of one more conflict that only signals a momentary respite before

the next one begins. The threat of death never leaves the combat

zone except after a battle when you realize how lucky you were to still be

alive.

As Marines, we respected the North Vietnamese's fighting

will.

They

were as tough as we, as dedicated, as brave and and courageous toward

their goals of winning, of inflicting the greatest pain and suffering upon

their enemy.

They

were as tough as we, as dedicated, as brave and and courageous toward

their goals of winning, of inflicting the greatest pain and suffering upon

their enemy.

That's why we walked through the body count in respect.

Man-for-man, they were our brothers in blood. We all knew that.

We didn't cheer at their defeat. In another time, another place, under

different circumstances, we might have fought on the same side.

Ideology separated us, but we were equals in Courage, Bravery and

Conviction. Our parallel willingness to die made us blood brothers.

After mopping up, we

left the battlefield and moved on, continuing our sweep.

A few months later we were on patrol in the same

sector. I had forgotten about the battle in the rice paddy

until we came upon the scene.

It was a bright sunny day. Life was

peaceful. The rice shoots were standing tall above the water.

Silvery spots danced on the surface as the wind tickled the water, causing

the sun's reflection to create a shimmer.. Clumps of white

clouds lazed overhead and the bright green verdant view of the Vietnam

landscape framed the scene into a soft watercolor that might have rivaled

any travel poster.

We took a break at the spot.

I began to search for battle signs--perhaps

a shell casing, or a used compress, a helmet, some artifact that might

denote we had been here turning the rice paddy water red with our blood.

The battle area had been picked clean either by the farmers who wanted

their land returned to its original state, or by the Viet Cong who used

anything and everything left behind.

I began to search for battle signs--perhaps

a shell casing, or a used compress, a helmet, some artifact that might

denote we had been here turning the rice paddy water red with our blood.

The battle area had been picked clean either by the farmers who wanted

their land returned to its original state, or by the Viet Cong who used

anything and everything left behind.

Tired, sweaty and empty handed

I sat down next to a paddy dike. I removed my helmet and

leaned back against the slope of a small mound of dirt. That's

when I saw it--my artifact--the bloody leaf.

At first I didn't recognize the rusty color

clinging to the bright green "V"-shaped leaf that arched upwards from a

long stem and appeared to be sunning itself. I slipped

my finger under the leaf and lifted it slightly, religiously, to inspect

it more closely.

The dried blood had survived; it was now

part of the leaf. I sat for a few moments staring at it. I

wondered whose it was--ours or theirs? I wondered how old the owner

of it had been? I wondered about his friends, mother, father, wife,

children, brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles?

brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles?

I touched the dried, caked surface where

the blood had been embossed into leaf's veins, as though hoping to dial up

some mysterious spiritual station that might lead me to its owner's life,

to see who he was, what he was like. There was something

special about touching it--both life and death in one body. It

seemed the two had blended into one, the alpha and omega, the binary of

existence. I felt the answer to the meaning of life and death was

captured in the molecules of the leaf--that it held some answer to all my

questions only I couldn't translate them.

Then the command came for us to "saddle up

and move out." I sat for an extra moment, pondering whether I

should pick the leaf and take it with me as a memento, a reminder of the

devastation of war. I thought about sending it home to my fiance' and

having her press it into a book so that years later I could open it and

touch and smell and ponder some more, hopeful that the answer to my

questions might come with age and wisdom.

Then the command came for us to "saddle up

and move out." I sat for an extra moment, pondering whether I

should pick the leaf and take it with me as a memento, a reminder of the

devastation of war. I thought about sending it home to my fiance' and

having her press it into a book so that years later I could open it and

touch and smell and ponder some more, hopeful that the answer to my

questions might come with age and wisdom.

"Saddle up! Move out!"

I reached for the leaf. My fingers were

poised near the stem. Then they froze. I couldn't pick it.

It belonged here, in a rice paddy in Southeast Asia, not in a book.

Life and death were not mine to pick, only to ponder. I took one

last look at whomever's blood it was that anointed the leaf and realized

that everything recycles. The blood of the dead gives life to

the new.

I stood and placed my helmet

on my head.  Then I saluted the blood-stained leaf. I saluted

the bravery and courage of warriors

Then I saluted the blood-stained leaf. I saluted

the bravery and courage of warriors  fighting

for what they believed, and, at the same time, felt the sadness

and waste that resulted when people's viewpoints differ so much

they are willing to kill one another over their differences.

How sad, I thought, how terribly sad.

fighting

for what they believed, and, at the same time, felt the sadness

and waste that resulted when people's viewpoints differ so much

they are willing to kill one another over their differences.

How sad, I thought, how terribly sad.

When I returned to regimental headquarters, I

wrote a story about the bloody leaf. It was published in our paper.

Its theme was how the earth swallows the signs of war and recycles them

back to life, but leaves in that soil the Courage, Conviction and Bravery

of those who fertilized it with their blood.

. Then I forgot about the bloody leaf. I forgot

about it until this morning when I read about the new body parts being

found.

The story this morning reminder me that Terrorism

is the blood on America's leaf.