|

The

VigilanceVoice

The

VigilanceVoice

VigilanceVoice.com

Saturday--July

27, 2002—Ground Zero Plus

318

The Monkey Business Of Vigilance

Is Not Eating Them--The Monkeys!

by

Cliff McKenzie

Editor, New York City Combat Correspondent News

GROUND ZERO, New York

City, July 27--Ever have a bunch of monkeys save your life? I have.

Ever eat a monkey? I hope not.

My eyes were drawn to a

story in the New York Times this morning about the ill fate of rare

monkeys in Vietnam. Hunters are killing off some of the most beautiful

and gracious of our ancestors and eating them in elegant restaurants as

delicacies. In a way, they are eating our great, great, great, great,

great grandchildren, grand nieces, grand nephews.

I don't think there is a child alive who isn't awed by the antics

of a monkey. The biggest sour puss child who seems immune to laughter

breaks into a wide grin as monkeys cock their heads and scratch at their

armpits, hang upside down by their tails, or leap from branch to branch,

chattering and screeching in playful joy and respite. And nothing is

more fascinating than to have a monkey stare at you, its curious eyes

flicking all over your face, its leathery hands touching your nose and

mouth, exploring your countenance as though trying to remember exactly who

you are, and why you look so "funny."

|

But the fate of monkeys in

Vietnam seems foreboding. The lush, jungle nation of nearly 80 million

people has a taste for monkey meat as well as monkey blood. During the

Vietnam War, I walked through the narrow, clogged streets of Saigon and

Cho Lon and saw countless monkeys trapped in cages. You could order the

one you wanted. The merchants drained its blood and you drank it warm,

an alleged delicacy I never did or want to try.

Monkeys have always been my friends. Prior to joining the U.S.

Marine Corps, I was a senior in psychology at the University of Oregon in

Eugene. I was specializing in learning behavior, and spent a

considerable amount of time working in the University's primate lab. At

the time, we enjoyed the largest collection of wild monkeys west of the

Mississippi. The top billing for primate research at the time belonged

to Yerkes, a world renowned primate testing center.

|

I conducted various

learning tests on a variety of species, all wild monkeys, the best for

research. We used a Wisconsin General Testing Apparatus, measuring the

discrimination skills of the animals. After getting my "test monkey"

from the primate lab, I pushed a tray toward the monkey in the testing

room with various shapes or letters on it. The money had to figure out

which one had a raisin under it.

I loved the lab and monkeys and spent as much time with them as I

could. I talked to the simians, getting to know them probably better than

I knew most humans. They were rare, ranging from Madagascar ring-tailed

lemurs to squealing spider monkeys that ignited the housing room with a

shrill cacophony whenever you entered.

When I arrived in Vietnam, I felt welcomed by them in this the full

of their brothers and sisters. On patrols deep in the jungles, the

sounds of the monkeys was a "safe sound." It meant everything was Okay.

But when the monkeys fell silent, and the jungle seemed to suck in a deep

hesitant breath, you knew danger lurked--that an ambush or the enemy was

close by.

On one patrol we were moving through the dense underbrush. I was

listening to the sounds of the jungle, keying in on the monkeys with whom

I had continued a close relationship. Suddenly, there was silence,

following a burst of their raucous chattering, sending out a warning.

I halted our patrol and motioned for the men to spread out and take

cover. Ahead of us was a long column of Viet Cong bringing in

supplies. Had we kept moving we would have stumbled into the thick of

them. Because of the monkeys' alarm we instead set up an ambush and were

successful in our mission.

On other patrols, I had various encounters with monkeys. Our

ambush unit switched back and forth, half on alert, half sleeping, at

two-hour intervals. I'm a snorer, so I always dug a hole in the earth and

put my cover (soft hat) down in the cup of earth I dug with my bayonet and

buried my face in it while I slept, so that if I snored, the ground would

absorb the noise and my snoring would not alert any enemy patrols (and

irritate my fellow marines).

|

One night I awoke startled.

Crouching in front of my face, just a few inches from me, was one of my

simian friends. It quizzically stared at me, its long, leathery fingers

clutching the bill of my soft cover. My heart raced as I reached for my

weapon, not yet sure in the haze of awakening what the figure was. Then

the monkey peeled back its lips, almost as if smiling, and jerked my cover

away. He stood for a second staring at me like some errant, playful child

who was "stealing" my toy, and then scampered off into the moonlight

night, swallowed by the leafy green of the Vietnam jungle.

I wanted to laugh, but constrained myself. In

the madness of war, I was befriended in an odd way by a creature, who

perhaps knew I was a "monkey man," a term often used in psychology to

identify those who tested monkeys versus those who tested rats. We called

rat testers--"rat people"--a lower form of research, we affirmed.

These experiences, three decades old, streamed back to me as I read

the Times article about the endangered primates.

I was revolted as I continued to read. I couldn't imagine people

eating the delicate, beautiful creatures whose biggest joy in life, at

least in my mind, is making people laugh at their antics.

|

The more I read the more I realized I owed

the monkeys. They had helped save my life and the lives of my buddies from

an enemy ambush. More than once I had used their silence as a warning

during more than 100 patrols and missions I participated in. They

became my Sentinels of Vigilance, alerting me to danger, keeping me

appraised of the fine line between life and death.

The idea that rich Asians were coming to Vietnam to feast on the

exotic meat stripped from rare simian bones, upset me. It made me think

of cannibalism rather than a gourmand ritual.

|

|

Cat Ba langur |

One of the

most beautiful and rare monkeys considered the "feast for a king" is the

Cat Ba langur. It is heavily hunted, and, according to NY Times

travel writer Connie Rogers, who just visited the country, is a top menu

choice for over 100,000 Asians who visit Cat Ba island each year.

|

|

Grey-shanked

Douc langur |

Two of the rarest monkeys, the Cat Ba langur and

Delacour, are projected to become extinct in the next few decades, reports

the American Museum of Natural History. One-fifth of the world's 25 most

endangered primates live in Vietnam.

The country is rich with vanishing primates--rare Eastern

Black-crested gibbons, douc langurs, Ha Tinh langurs and Tonkin snub-nosed

monkeys.

A battle is being waged to preserve them. Conservationists have

established rescue missions to save the dwindling simians from the cooking

pot and from trappers who seek to capture and sell them as pets. Both

acts are illegal, but policing the dense jungle is more than a challenge

for a government with its hands full in rebuilding its nation.

|

In a world filled with

Terrorism of all degrees, one might think a monkey's fate is low on the

totem pole. But perhaps not. Perhaps saving a monkey's life is more

important than finding Osama bin Laden and taking his. At least, that is,

to a child.

I've always looked at monkeys as children of laughter. They

force a child to smile. The thought of someone eating them put a knot in

my gut. It made me wonder how to apply Vigilance to the Terrorism of

monkeys.

Vigilance is an inclusive rather than exclusive venture. When one

thinks of combating Terrorism, the first thought is bolting the door to

defend against masked strangers tossing satchel charges at door steps.

But Vigilance is more than being defensive, it's an offensive attitude.

Often, it comes to focus stronger when emotionally charged than when

physically threatened.

The benchmark question of Vigilance is: "What's good for the

children's children's children?"

Certainly, eating monkeys, especially rare, beautiful ones, doesn't

hit the top of the charts. By nature, I'm not an animal rights activist.

I'm not a garbage can banger who walks down the street claiming the sky is

falling if we don't save the spotted owl. But I do set aside my

garrulous nature to stop and think about the kids--not only the human

kids, but the children of the monkeys as well. After all, their great

great grandparents helped save my life.

|

I also can't help but feel some close

natural connection, some ancestral link considered by many evolutionists

to be the dividing line between us humans, who can choose the right or

wrong thing, and our tree-swinging buddies who operate solely from

instinct.

I also understand mankind’s need to expand. In Vietnam, as with any

nation that progresses, the forests are being farmed for trees to build

the country and supply natural resources. A monkey has little Voice in

its own defense--either from ecological intrusion or from hunters who want

their meat to sate the pallets of their customers.

But I can’t turn my head to the issue of Vietnamese monkey

plight.

.jpg) |

Terrorism is about Complacency--the lack of concern. Complacency

is fed by Fear and Intimidation. One of our great Fears is impotency on a

major issue—that lack of ability to “make a difference.” Intimidation is

the other ingredient: "What can I do about the problem with monkeys being

eaten in Vietnam when America can't even find Osama bin Laden?"

Complacency thrives in a state of immobilization, a state of

resignation. It grows in a myopic view that makes it hard to see how our

“little Voice” can do anything, as well as by the stunted nature of our

vision.

Vigilance, on the other hand, gives us a much longer, richer,

deeper view to the horizon and beyond.

If we think about monkeys as our far-distant children, how many of

us would stand for others eating them? If someone told you your child

was wanted on the menu for people who like the taste of "little things,"

how would you react?

It's one thing for a creature to be taken to become a pet, or part

of a zoo, but quite another for it to be served as a main course, ending

its life, and its ability to procreate. It seems to me that one of the

saddest acts of Terrorism in our world today is eating "rare monkeys."

It would be easy to neglect this small issue in light of larger,

far more pressing ones that agitate the world.

But Vigilance is about vision. It's about seeing far into the

future, to the children's children's children's children benefit..

While we might think we can't do a damn thing about the eating of monkeys

in Vietnam, that may not be true at all. And, doing something about it

may be far more important to our children than rolling bin Laden’s head

down Main Street, or prosecuting the financial “monkey eaters” at Enron

and Arthur Anderson, or turning Martha Stewart into our our lady with a

scarlet letter on her forehead.

Lack of “monkey vision” might deprive our children of a precious

association with a distant cousin, might reduce the awe in their eyes when

they see one in a zoo, or on Discovery Channel.

|

There are things you should consider

While you are at the zoo,

For as you watch the monkey,

The monkey's watching you.

At dinner when you tell your mom,

"The monkey's a disgrace."

The monkey talks about the kid

With mustard on his face. |

|

from

Zoo News "Do's and Don'ts" |

Vigilance demands we make a

stand, that we draw a line in the sand and add some mortar or concrete to

it. In the long run, we don’t want our children to think we sat back and

did nothing as the monkeys of the most rare and precious genre were

consumed by tourists who flocked to Vietnam to eat the last remaining

species of our children’s most distant relatives.

Complacency tells us to turn our head, to leave the rescue of the

monkeys to someone else, someone better equipped—to the “do-gooders.”

But Vigilance demands that we toss Complacency overboard, and that we make

some effort, however small, as a sign to our children that one can take a

stand—that one grain of sand can ultimately become a beach.

. Maybe it's just sending some important greenbacks to one of the

rescue camps in Vietnam that attempt to protect the rare monkeys. Or,

perhaps it's rallying the kids in the neighborhood to write letters to the

head of Vietnam, or to our U.S. Trade Division that offers money and

outlets for Vietnamese commerce.

|

Maybe it's a simple

as talking the “monkey issue” over with your kids, and letting them know

you care about their feelings, asking them what they think they can do,

what the family can do, to help out the at-risk monkeys. A favorite

children's song would be changed to No More Monkeys Jumping on the Bed

(see book on right).

Vigilance is a lot about listening and learning what’s in your child’s or

loved one’s heart.

Vigilance takes Courage, Conviction and Right Action to be set

into motion. A child who sees his or her parents, grandparents, uncle,

aunt, or loved one concerned about a monkey's future, takes a second look

at his or her role in the world. He or she sees people who are

concerned—not afraid to be a “grain on a beach.” The Vigilance

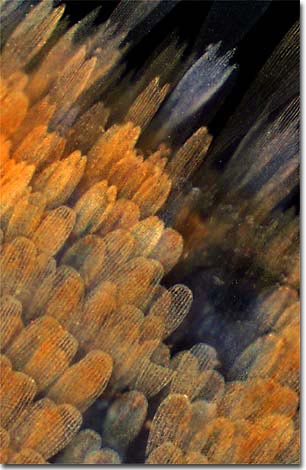

expressed over a monkey’s future can have the “butterfly effect.” The

effect is said to start with the ripple of a butterfly’s wings upon the

water, very slightly moving it, but as it builds and grows, it can result

in a giant wave culminating on some beach thousands of miles from it

origin.

|

|

Rippling Butterfly Wing |

I owe the monkeys maybe my life, so I have an extra

obligation. But I also have grandchildren who need to learn how to be

more Vigilant than Terrorized by life. They need to know their Voices,

however small and seemingly insignificant, have a right to be heard.

They need to know they can stand for something even though others may not

stand with them for whatever reason. And, I, as a Parent of Vigilance, a

Grandparent of Vigilance, a Citizen of Vigilance, owe it to them to show

my concern for the monkeys.

Below, I've listed some websites you can browse. (Note:

They have great pictures of the monkeys on them)

To sum up my Vigilant point, I ask--"Would you eat a rare,

endangered species monkey just because it tasted good?" If not, maybe you'd like to show your children the power of one

Vigilant Voice--yours.

Vietnamese Embassy--www.vietnamembassy-usa.org

Endangered Primate Rescue Center--

www.primatecenter.org

Cuc Phong National Park--http://nytts.org/vietnam/

NY Times Article--http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/28/travel/VIETECO.html

Go To July 26--Vigilance Not Vigilantes

©2001

- 2004, VigilanceVoice.com, All rights reserved - a ((HYYPE))

design

|

|

.jpg)